There are longstanding concerns about foreign service providers processing European personal data. Ten years ago, Edward Snowden revealed the extent of secret surveillance conducted by the US and its allies, as well as their reliance on US service providers. In 2018, the newly enacted US CLOUD Act sparked concerns about US government access to European personal data, even when the data are stored in Europe. Today, some are calling for the use of European providers who are immune from foreign jurisdiction.

- In July 2024, for example, the CNIL opined that processing of the most sensitive data must not be subject to a risk of unauthorized access by foreign governments. Instead, processing such data required a service provider that is “exclusively subject to European law”.

- Further, in March 2024, the EDPS decided that the Commission’s use of Microsoft 365 infringed data protection law. It noted that foreign laws on government access with extra-territorial reach presented a compliance challenge. It concluded, inter alia, that the Commission had failed to implement effective security measures to prevent unauthorised disclosure of data processed in the EU. Microsoft has since appealed the EDPS decision.

In light of the above, at the Cloud Legal Project, we set out to answer two questions:

- First, does a cloud provider breach the GDPR when it discloses European personal data to the US government in compliance with a US production order?

- Second, does a European customer breach the GDPR when it uses a US cloud provider to process European personal data, if that data can be subject to US production orders?

- A Cloud Scenario

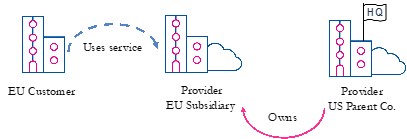

To illustrate this issue, consider a typical scenario. Suppose that a company registered in the Netherlands uses the services of a US hyperscaler to store personal data about its employees. It contracts with the US provider’s European subsidiary, which is registered in Ireland and is owned by a parent company registered in the US. So, we have three companies: a European customer; the US provider’s EU subsidiary; and its US parent company.

Figure 1: a European customer uses a US cloud service

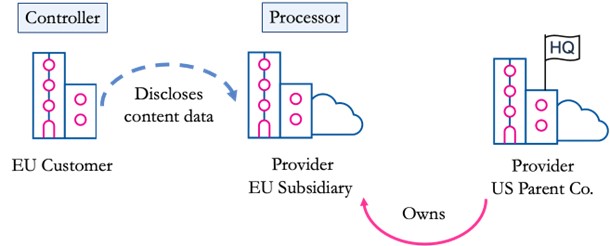

In this scenario, the customer typically acts as the controller for the data it stores in the cloud (which we refer to as “content data”). The provider acts as a processor, processing content data on the customer’s behalf. The situation is more complicated for service-generated data, such as metadata, which the provider collects and can process for its own purposes. So, to keep things simple, we focus on content data here.

Further, let’s assume that the European customer instructs the cloud provider to store the content data on servers in the EU. In other words, it uses a localised cloud service like the AWS Europe Region. In this case, the US provider’s subsidiary does not transfer content data to its US parent company as part of its routine operations. As above, the situation is more complicated for service-generated data, some of which the provider might still transfer to its US parent company. For simplicity, we focus on content data here.

Figure 2: Typical controller and processor roles

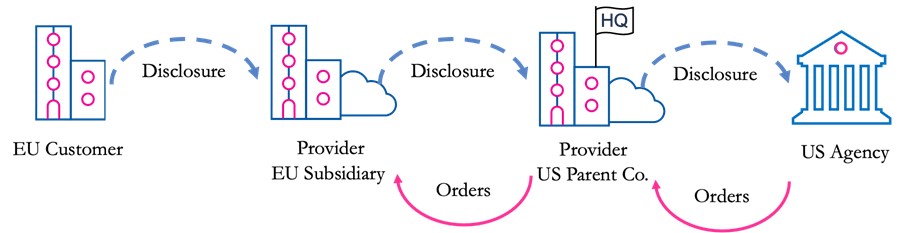

Now, suppose the US government issues a production order compelling the cloud provider to hand over European personal data stored by the European customer. This could be either:

- a US law enforcement agency seeking evidence in a criminal investigation under the Stored Communications Act, as amended by the CLOUD Act; or,

- a US intelligence agency seeking foreign intelligence information under FISA Section 702.

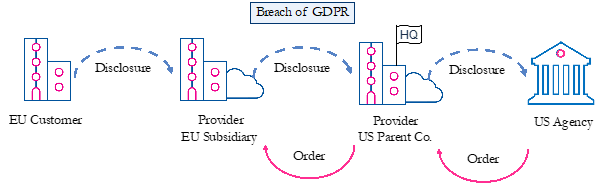

The US government can issue such production orders to the US parent company for any data within the company’s “possession, custody, or control”, regardless of where data are stored. This includes data processed by the provider’s EU subsidiary, since the US parent company can order its subsidiary to grant it access to the data. As a result, the subsidiary’s data are within the parent company’s legal control. The extra-territorial reach is explicit under the CLOUD Act and we argue that the same applies to FISA Section 702 as well. So, faced with a binding US production order, the US parent company orders the EU subsidiary to disclose the data, which the parent company then discloses to the US government, as set out in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Disclosure following a US Production Order

- Disclosure in breach of the GDPR

We argue that the cloud provider’s disclosure pursuant to a US production order can breach the GPDR in three ways. First, as a processor, the provider’s EU subsidiary must only process content data on the instructions of the customer, unless it is required to process the data by EU or Member State law. So, when it discloses data to its US parent company without instructions from the controller and when required to do so only by US law, then it breaches Article 29 of the GDPR.

Admittedly, cloud providers will typically include terms in their standard contracts permitting them to disclose customer data when necessary to comply with a government order. However, it is unclear that the inclusion of such a broad and generic reference to compelled disclosure in a standard contract is sufficient to establish that the customer has instructed the provider to disclose personal data to the US government. If providers had intended to obtain formal instructions from the customer as controller to disclose data to the US government, they could use clearer and more detailed terms.

Second, the provider becomes an independent controller for the purposes of the disclosure. This means that it needs to have lawful grounds for this processing under Article 6 of the GDPR. Yet it is not clear on which lawful grounds the provider could rely. The need to comply with US law alone does not provide lawful grounds under Article 6(1)(c), which is limited to EU and Member State laws. Further, the EDPB and EDPS have opined that the controller’s legitimate interests cannot provide a valid lawful ground under Article 6(1)(f) either. This ultimately depends on the balancing of interests in a specific case.

Third, as a controller, the provider must comply with purpose limitation under Article 5 of the GDPR. In this case, the provider transmits data for the purpose of disclosure to the US government. The question, then, is whether such disclosure is compatible with the initial purposes determined by the European customer, as the original controller, at the point of collection. This depends on what the customer’s initial purposes were and factors such as the links between the two sets of purposes; the context in which data were collected; the nature of the data; and the possible consequences for data subjects.

By contrast, cloud providers could disclose data to the US government if they were required to do so under EU or Member State law. For example, European airlines can disclose passenger name record information to the US government under the EU-US PNR Agreement. Similarly, European financial institutions can disclose financial information to the US government under the SWIFT II Agreement. Both agreements permit such disclosures in order to combat terrorism and other serious crimes. The EU and the US are also negotiating a CLOUD Act Agreement, which could permit cloud providers to disclose personal data to US law enforcement agencies. However, the agreement would not cover disclosures to US intelligence agencies.

In sum, absent such a basis under EU or Member State law, when a provider processes personal data for the purposes of disclosure to the US government, it:

- appears to breach the prohibition on processing without controller instructions under Article 29 of the GDPR; and,

- might also breach the principles of lawfulness and purpose limitation under Articles 5 and 6 of the GDPR.

Figure 4: The provider’s disclosure appears to breach the GDPR

3. Controller obligations

US production orders present a challenge for the European customer too. This is because, as a controller, it has a duty under Article 28 of the GDPR to only use a processor that offers sufficient guarantees of compliance with data protection law. So, the European customer must be sure that US cloud providers can offer such guarantees, despite the data they process being potentially subject to US production orders.

In our view, this doesn’t necessarily require the use of cloud providers who are only subject to European jurisdiction. But it does mean that European organisations need to carefully consider whether their use of US cloud providers complies with the GDPR, in light of the risk that US government access poses to the rights of European data subjects.

In some cases, especially for highly sensitive data, European customers might need to put in place risk-mitigating measures, such as European data trust models or end-to-end encryption, including new confidential computing techniques. We explore such a risk-based approach in more detail in a forthcoming paper.

In the meantime, if you’re interested, you can read our draft paper on SSRN here: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4911552. We develop the above analysis in detail and cover lots more issues, including:

- whether a cloud provider’s disclosure to the US government breaches security obligations under Article 32 of the GDPR; and,

- whether the provider’s disclosures to the US parent company and to the US government constitute unlawful transfers under Chapter V.

As this is a draft paper, we’re actively looking for comments. So, if you have any thoughts on our analysis, please don’t hesitate to contact us at cloudlegalteam@qmul.ac.uk or add Dave Michels on LinkedIn.

The authors would like to thank all participants in a workshop held at the Vrije Universiteit in Amsterdam in May 2024 for sharing their views on the analysis, and Assistant Professor Silvia de Conca for organising the workshop.

This research has been conducted by members of the Cloud Legal Project, Centre for Commercial Law Studies, Queen Mary University of London. The authors are grateful to Microsoft for the generous financial support that has made this project possible. Responsibility for views expressed, however, remains with the authors.