March 8th marks the International Women’s Day, a global occasion to reflect on the importance of achieving gender equality and the well-being of women in all aspects of life. ALTI joins this reflection with a piece by Prof. Kim Barker on the dire situation of women online, and specifically in the gaming community: while this topic might appear trivial, the harassment and violence experienced by women online translates into their exclusion from an entire entertainment sector, from a chance of socializing, and from a multi-billion industry.

By Professor Kim Barker is Professor of Law at Lincoln Law School, University of Lincoln, and founding Director of Europe’s first Observatory on Online Violence Against Women. She can be found on X @BabyLegalEagle or contacted via email at kbarker [at] Lincoln [dot] ac [dot] uk.

Online violence against women (OVAW) (also known as cyberviolence against women (cyberVAWG) is not a new phenomenon but neither are the misogynistic and patriarchal attitudes that underpin such behaviours. OVAW is now a well-acknowledged obstacle to gender equality in digital spaces. Behaviours amounting to OVAW include – amongst other things – text-based abuse, image-based abuse, trolling, the making of threats, bullying, as well as doxing, cyberflashing, and dogpiling (cyber-mob attacks). Where directed at women in online environments, these forms of harassment threaten their ability to participate fully and freely in digital life, across social platforms, websites, messaging apps, and online games. That these issues remain largely unchecked and unaddressed presents ongoing participatory problems for women, but also poses questions about the effectiveness of the regulatory responses to such exclusionary behaviours.

Online Violence Against Women Gamers – A 30 Year+ Problem

Online harassment, abuse, and violence is not a problem which is new to games but is a problem which dates back to the origins of online games. From the earliest interactive environments, issues such as virtual rape, and virtual sexual abuse have occurred. Reports from 1993 in LambdaMOO detail ‘cyberrape’, alongside incidents of ‘virtual rape’ reported in Second Life across 2007, and disturbing numbers of reports of sexualised and violent content in Habbo Hotel in the early 2010s. These have been mirrored with reports of sexual harassment being rife in Horizon Worlds but none of these are isolated instances. These are incidents which are not unique to today’s metaverse, despite the shock-inducing headlines of early 2024 indicating that gang-rape in the metaverse is a ‘first’, suggesting that incidents like this are the beginning of a ‘new future’. This is not the case – these incidents are not unique to the metaverse and are not, despite the harm attached – that we do now recognise in online contexts – novel problems of the present. These are issues which have been in existence for as long as women have sought to interact and play equally in games.

These selected examples offer a holistic picture of the scale of OVAW in games, with numerous experiences of women in games highlighting behaviours that have historically gone under-addressed and remain unchecked. Women have been experiencing 30+ years of over-sexualization, second class status, and abuse in games. These behaviours have come to the fore more recently as part of a wider discussion surrounding online safety. But this is a classic example of being late to the party in the context of online games, and discussions of online safety ignore the long-standing cultural issues in games.

A Culture of OVAW in Games

In 2012, the picture painted of video games was far from great, with 60% of women reporting experiences of harassment, whereas 79.3% of those playing games highlighted the prominence of sexism in these spaces. Moreover, and far from surprising in light of the incidences of sexual harassment in gaming environments, in 2012, 20% of women reported being ‘bothered’ outside of a game too. The experiences reported by women in games from 2012 onwards broadly reflects these statistics. Also in 2012, Anita Sarkeesian drew attention to the experiences of women in games, and was rewarded with a Wikipedia page that allowed visitors to virtually beat her up. Again, this is not an isolated example of the prevalence of online violence against women gamers, not least because this was online albeit in a non-game environment. Perhaps the most high-profile example of the abuse, violence, and harassment facing women comes in the form of Gamergate – which evolved as the embodiment of a ‘rallying cry’ for those seeking to abuse and harass women in games, and became a coordinated attack campaign using the hashtag of the same name, while targeting Sarkeesian, Zoe Quinn and other women in games, including game developer Brianna Wu who alone received over 200 death threats. The effects of #Gamergate remain significant, with rape and death threats, fake news reports of the death of those targeted, and personal information of women being posted publicly online. In essence, this is an example of what Valenti calls ‘…[s]talking gone viral.’

These are not the only examples, with the so-called ‘Rape Day’ fiasco from 2019 presenting a much more recent instance of the horrific experiences facing women in the games industry, as well as women gamers. The game, ‘Rape Day’, allows players to harass and rape women, and kill people in the midst of a zombie apocalypse, and was initially released on games platform Steam in 2019, before later being removed. In contrast, it was never available via Valve even though Valve never actually condemned it. That such a game could be released for sale is in itself an indicator of the wider challenges surrounding attitudes towards women in games, often fostering ideas of women as objects for abuse. While abhorrent, it is not the first example of such a game – back in 1982, Custer’s Revenge was released, and it too had a focus on the rape of women as its gameplay, with added racism, something Gutiérrez highlights is a form of gender-based violence. But these are not the only games which encourage such behaviours or portray women as objects for abuse – they, together with games which have come much later indicate that there is a longitudinal problem that games have when it comes to women and how women are portrayed and treated within games, as well as within the game industry. Other game series’ have also attracted criticism for similar portrayals, notably one of best-selling games of all time – Grand Theft Auto V.

In 2021, the experiences of women in games have hardly improved when compared to those in 2012 despite that fact that OVAW is no longer an emerging phenomenon. That things are no better is indicative of a string of failings from industry as well as the legal system. In 2021, 28% of female gamers reported being sexually harassed in some form while gaming. Similarly concerning, is the prevalence of sexual harassment in games, with 32% of gamers reporting some form of it.

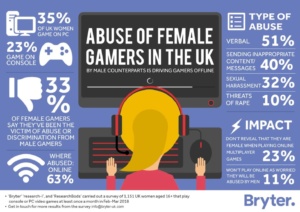

Figure 1: Abuse of Female Gamers in the UK (Bryter).

And yet, today, the picture is not much more promising. The number of examples of the abuse and harassment women suffer in order to play games is overwhelming. While examples indicate the long tail of OVAW in gaming environments, statistics indicate that there is a much bigger challenge facing games and the gaming industry when it comes to women. In Britain, these statistics are even more stark, with 49% of female gamers stating that they have experienced online abuse. This is even more prolific for those aged 18-24, where a staggering 75% report online abuse, and 80% receive sexual messages. 40% of female gamers have experienced or received verbal abuse while playing online multiplayer games. In many respects, these statistics suggest that the situation for women in online games has deteriorated since 2012, and yet, this deterioration has occurred across the period during which discussions of online harm and online safety have become most pronounced nationally and regionally. Cumulatively though, this is indicative of a wider, industry-wider challenge, as Thorne highlights, ‘When it’s one call-out, it’s a problem with a person, When there’s a ton of call-outs, it’s a problem with the industry.’

In many respects, this is indicative of a culture of online violence against women in games. These spaces are integral to our interaction, especially post-COVID, and yet the scale of OVAW raises – as yet unanswered – questions about appropriate regulatory and legal responses. Given the growth in gaming, it is high time that these spaces became safe for all players, not just men.

Regulatory Responses to Online Violence Against Women Gamers – Room for Improvement?

There has been very limited regulatory response to OVAW against gamers. Where there have been developments, these have tended to emerge against a backdrop of internet regulation more broadly, or reforms to update internet laws. Through so-called duties of care models, to legislation to address eSafety, or cyber violence featuring in legislative proposals, the dominant narratives surrounding regulatory responses, especially those from the legal system, have focussed on online safety, rather than tackling pernicious forms of behaviour through nuanced regulatory responses beyond simply legislative reform. Few of these initiatives address OVAW – neither directly nor indirectly.

Where there are responses to online harms – such as those seen with the Digital Services Act in Europe, or the Online Safety Act in the UK, introducing so-called ‘world leading’ provisions to address illegal content, little attention has been paid to the long-standing abuse, harassment, and violence that women in games and gaming environments have experienced – and continue to endure. In introducing legislation to address online harms, the emphasis falls not on the illegality of the content, but rather on the risks of harm posed by various categories of ‘priority’ content which require action, though the assessment of what is illegal will be left to platforms themselves. Where much of the abuse or harassment women experience in games is unpleasant, only a small proportion is likely to reach the required legal thresholds for action. Even where such content does, few, if any, of the provisions introduced in the pursuit of online safety require action against individual pieces of content – rather they are designed to operate with a much wider remit. They are therefore, not per se, content regulation. They also leave much to be desired in the protection – or otherwise – of human rights. And this presents something of a tension when it comes to addressing OVAW against gamers. To leave OVAW unaddressed presents human rights challenges for women in that they are being forced out of online environments, prejudicing their participatory rights. Yet at the same time, should online safety laws be used to target individual posts, messages or pieces of content, this presents significant freedom of expression concerns alongside those attached to overzealous content moderation.

Going forward, to meaningfully tackle these behaviours, there are a number of additional considerations that can be made. Law enforcement and judicial systems must move away from traditional ideas of making police reports offline – these should be possible directly from the game or environment where the harm or behaviour has been encountered. Women suffering online abuse should not be told they cannot report such behaviours online. Similarly, reports that are made to law enforcement concerning OVAW should not automatically become a matter of public record – unless and until there is a judicial outcome. OVAW should be appropriately defined in legislation – with agreement if at all possible – to prevent the conflation of different behaviours. Where guidance or codes of conduct are suggested, these must be rigorously developed, and must include consultation with a wide range of industry, independent experts, as well as stakeholders. And, more must be done to challenge the underlying societal and online misogyny which pervades games and game environments. Striking a balance between different exercises of human rights must also be managed with care to ensure women have the ability to participate, all while ensuring expression rights are upheld. Other promising initiatives that have potential to transform the experiences of women in games, should also be explored away from the legislative arena, such as the transformation of female game characters, such as Lara Croft’s evolution, moving away from the ‘male gaze’ and away from sexist depictions into more normalised portrayals. These are isolated, incremental developments rather than wholescale change. These are also driven by industry insiders, and are far from a collective regulatory response.

OVAW in Games – A Long-Standing Challenge but Time to Accelerate Progress?

Legal regulation and isolated instances of change within games and game companies are potentially positive steps. That said, they alone cannot encapsulate the whole-scale change that is required in order to reduce, if not eradicate, OVAW in games. While women make up a significant portion of video-game players, they are still to have equal representation in the industry more broadly – with women making up a minority of game developers. Even where women dare to suggest that they can have a seat at the table – such as Wu and Quinn, the backlash they receive is almost as significant as the challenges of OVAW in games to begin with, if not more pronounced. While these attitudes and inequalities persist, it is going to be incredibly difficult to change the culture of the sector, from developers down to players. Where such profound inequalities blossom, prevailing sexist attitudes are also likely to linger, with female players likely to be told, repeatedly to leave games alone or to ‘shut up… make me a sandwich.’ Representation is essential, much like improved responses from law enforcement to reports being made of online violence. In conjunction with this, it is essential that legal provisions recognise the underlying behaviours of OVAW and are capable of application to gaming environments.

There remains much room for improvement, all while recognising that different games have different characteristics and features, and no system of legal regulation can address each set of nuanced spaces specifically. That said, misogyny, abuse, sexual harassment, and OVAW in games pre-dates social media (and the abuse it generates which drives women offline). And yet, it is predominantly because of social media and the (now) recognised harms posed by interactions and algorithms across these services, that we talk about online harms and online safety.

OVAW in games and against women gamers is a long-standing, pre-social media problem, and yet it is one which we continually overlook from a regulatory perspective. In doing so, we have failed not just women gamers, but women more widely, and rendered, without challenge, an entertainment industry hostile to women. That women are resigned to their status as fodder for abuse and violence in order to play games is an indicator of the size of the failing, and of the significant work which remains to be done across the gaming industry, society, but also the law. As we have marked Internet Safety Day on 6 February, and look towards International Women’s Day on 8 March, it’s time not just to invest in women, but to invest in the safety of women online.