This short article serves as an introduction to Thibault Schrepel’s latest working paper, “A Systematic Content Analysis of Innovation in European Competition Law” (open-access)

***

Economies are becoming more complex, with more transactions required to produce each product.1Hausmann, Hidalgo, Bustos, Coscia, Simoes, and Yildirim, The Atlas of Economic Complexity: Mapping Paths to Prosperity (MIT Press, 2014), pp. 18-20; Hidalgo and Hausmann “The Building Blocks of Economic Complexity”, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, Vol. 106, No. 26 (2009), pp. 10570-10575; McKinsey Global Institute (2013), “Disruptive Technologies: Advances that Will Transform Life, Business, and the Global Economy”; World Economic Forum (2018), “The Global Risks Report 2018”. This trend is attributed to the transition from an industrial to a knowledge-based economy, which relies heavily on digital innovation, i.e., information and communication technologies. Innovation plays a crucial role in defining competitive dynamics and market boundaries.2Damanpour, “Organizational innovation: A Meta-Analysis of Effects of Determinants and Moderators”, Academy of Management Journal, Vol. 34, No. 3 (1991), 555-590 (innovation is positively related to firm performance); Yang, Li, and Li, “Mechanism of Innovation and Standardization Driving Company Competitiveness in the Digital Economy” Journal of Business Economics and Management, Vol. 24, No. 1 (2023), 54-73 (the level of innovation and standardization of a company drives its competitiveness); Geroski, “Innovation as an Engine of Competition” in Mueller, Haid and Weigand (Ed.), Competition, Efficiency, and Welfare (Springer, 1991), pp. 13-26; Jorde and Teece, “Antitrust Policy and Innovation: Taking Account of Performance Competition and Competitor Cooperation”, Journal of Institutional and Theoretical Economics, Vol. 147, No. 1 (1991), pp. 118-144; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (2015), “The Innovation Imperative: Contributing to Productivity, Growth and Well-Being” (calling innovation a “key driver of economic growth and development”); Petit and Teece, Innovating Big Tech firms and competition policy: favoring dynamic over static competition, Industrial and Corporate Change, Vol. 30, No. 5 (2021), pp. 1168–1198.

In light of this, one might wonder about the conceptual role of ‘innovation’ in antitrust law. More specifically, is there a coherent theory of innovation in competition law cases? If so, what is the impact of this theory on competition law outcomes? Does the theory take into account all aspects of innovation, or does it discriminate between characteristics? Is the theory consistent with recent findings in the literature? If not, how does the lack of theory affect competition law outcomes? Does the literature provide guidance to courts and agencies on how to develop a unifying theory?

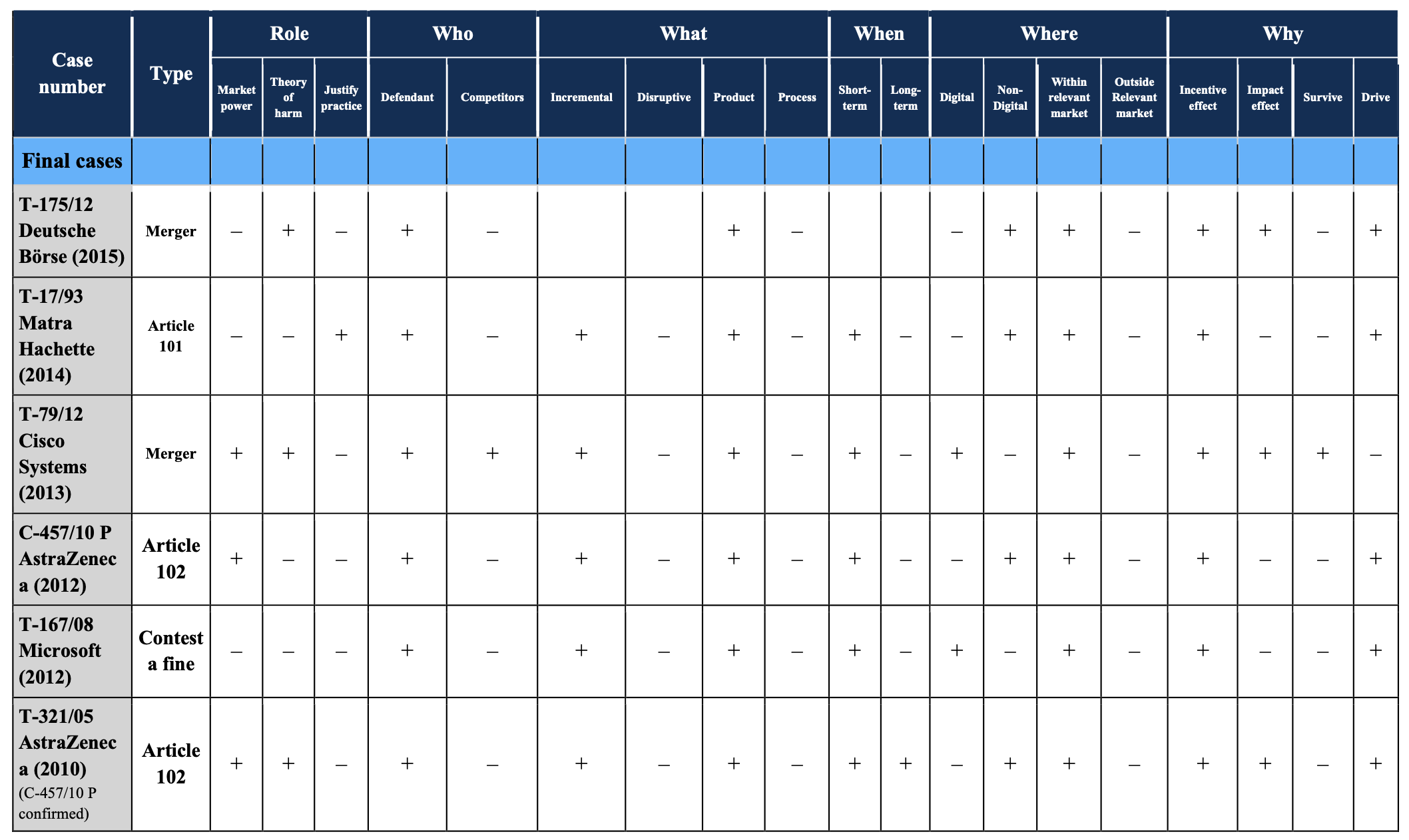

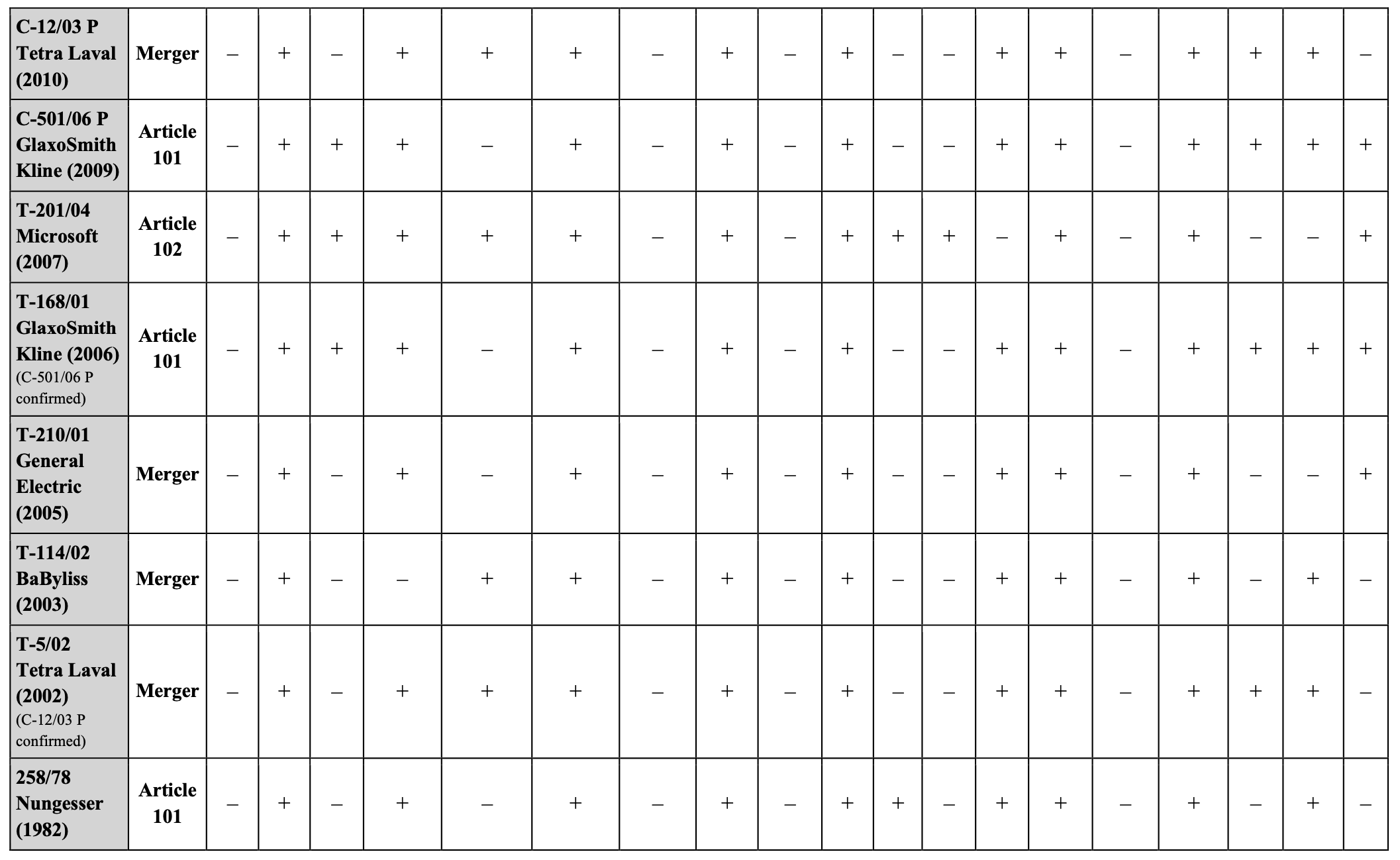

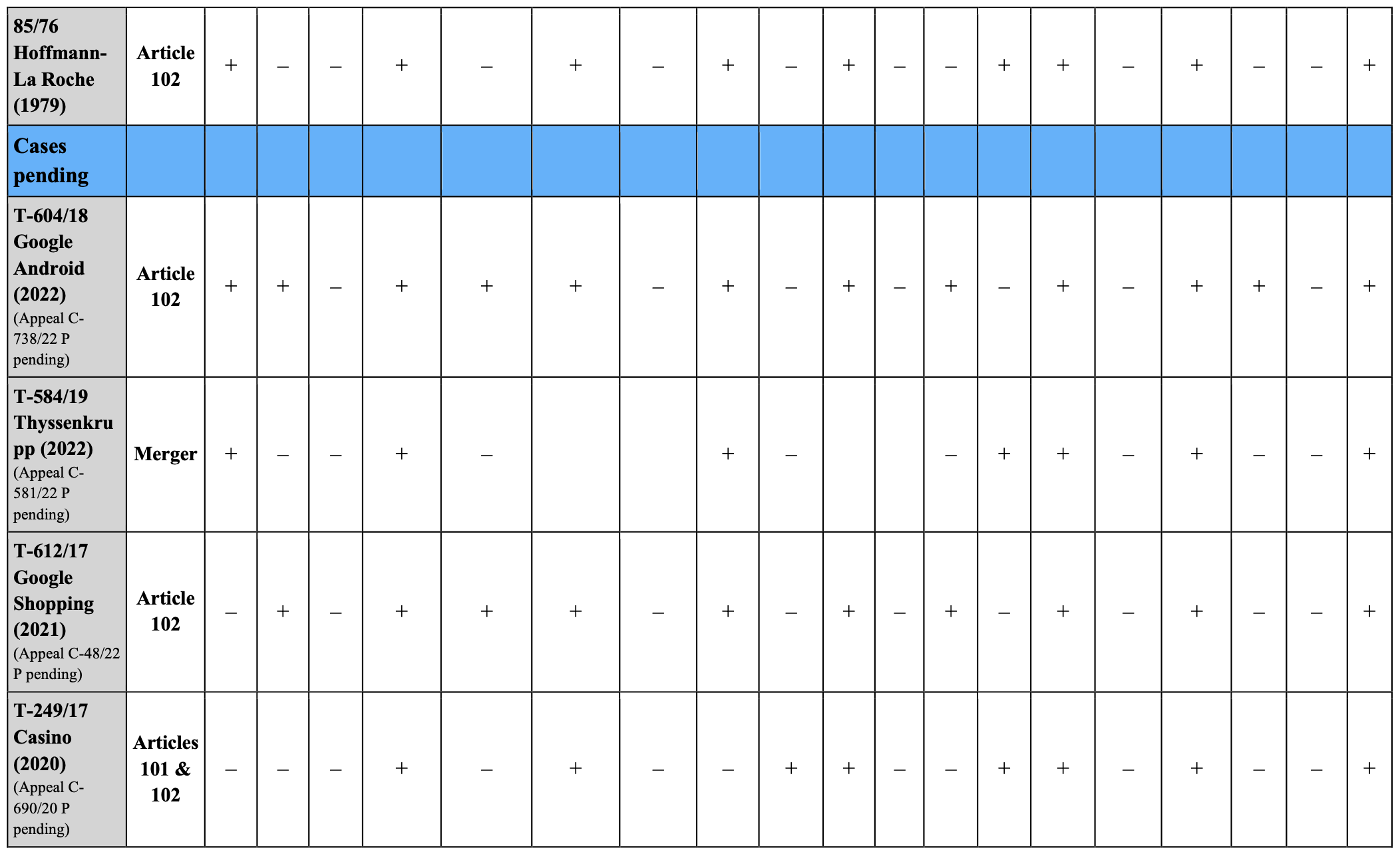

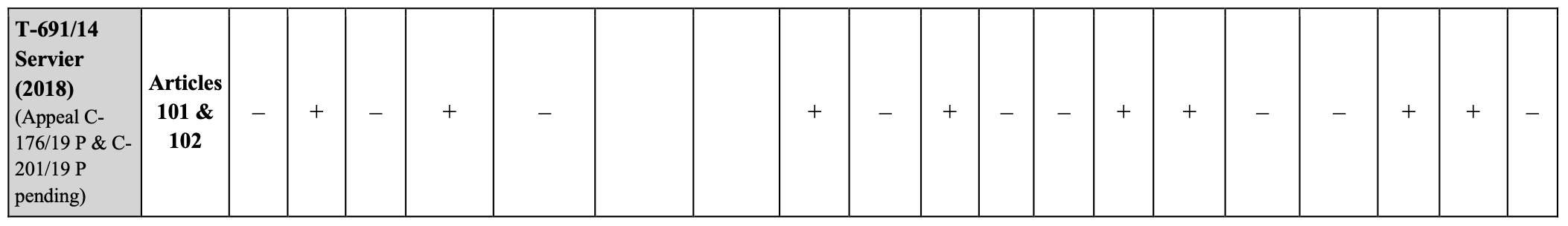

In “A Systematic Content Analysis of Innovation in European Competition Law”, Thibault Schrepel analyzes the 5 Ws of innovation, namely, who, what, when, where, and why.

Regarding the “who,” this article documents whether EU courts focus their analysis on defendants, plaintiffs, or both. With regards to the “what,” we focus on whether EU courts are dealing with product innovation (“a product innovation is a new or improved good or service that differs significantly from the firm’s previous goods or services and that has been introduced on the market”)3OECD/Eurostat (2018), Oslo Manual 2018: Guidelines for Collecting, Reporting and Using Data on Innovation, 4th Edition, The Measurement of Scientific, Technological and Innovation Activities, OECD Publishing, Paris/Eurostat, Luxembourg, pp. 70 or process innovation (“a new or improved business process for one or more business functions that differs significantly from the firm’s previous business processes and that has been brought into use in the firm”).4Oslo Manual 2018 supra note 12, pp. 72.

Regarding “when,” the present article first studies whether EU courts look at innovation in the short-term (with variables that can already be computed) or long-term (with variables that are yet to appear, e.g., after a period of 3 years). We do not distinguish whether EU courts look at the effects of past practices or whether they (also) discuss the current and future effects on innovation and related incentives. EU courts discuss past and present variables to infer future effects, which would have made the distinction artificial.

In terms of “where,” a first distinction is made between digital (used as a synonym for information and communication technologies) and non-digital cases, as EU courts may attach different attributes to innovation in related sectors. A second distinction is between considerations relating to innovation within the relevant market, as defined in each case, and innovation outside the relevant market. This distinction correlates with the analysis of incremental (i.e., extensions or modifications of existing products)5Ali, “Pioneering Versus Incremental Innovation: Review and Research Propositions”, Vol. 11, No. 1 (1994) Journal of Product Innovation Management, pp. 46-61 at 48. or disruptive innovation (i.e., products outside the relevant market with attributes initially inferior to those of existing products).6Larson, “Disruptive Innovation Theory: What It Is & 4 Key Concepts”, Harvard Business School Online (2016).

Finally, with regard to the “why,” this study documents whether EU courts consider the relationship between competition and innovation from an “incentive effect” or an “impact effect” perspective. The incentive effect refers to the idea that competition drives innovation (what we will call a competition-driven market, or “CDM”). The impact effect refers to the opposite idea of which innovation drives competition (which we will call an innovation-driven market, or “IDM”). We document the legal implications of these two competing conceptions of the relationship between competition and innovation. Finally, we also document whether EU courts view innovation as a survival strategy (i.e., a necessity) or as a driving strategy (i.e., leading the market or ecosystem in the desired direction).

For the rest, i.e., the in-depth analysis of the case law listed in these tables, and proposals to contribute to a theory of innovation in EU competition law that is applied with more consistency and take more parameters into account, see “A Systematic Content Analysis of Innovation in European Competition Law”.

Thibault Schrepel

@ProfSchrepel